The U.S. government has issued a sobering update on Social Security, warning that the program’s trust funds could be unable to pay full benefits within the next decade. While millions of retirees will receive a modest cost-of-living increase next year, the long-term forecast exposes deep structural problems that may leave future beneficiaries with smaller checks unless Congress acts soon.

Social Security Truth

| Key Fact | Detail / Statistic |

|---|---|

| Next Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA) | 2.8% increase in January 2026 |

| Trust Fund Depletion Date | 2034 (one year earlier than previously projected) |

| Post-depletion Benefit Level | About 81% of scheduled benefits payable under current law |

| Long-term Funding Gap | Equivalent to 3.8% of taxable payroll over 75 years |

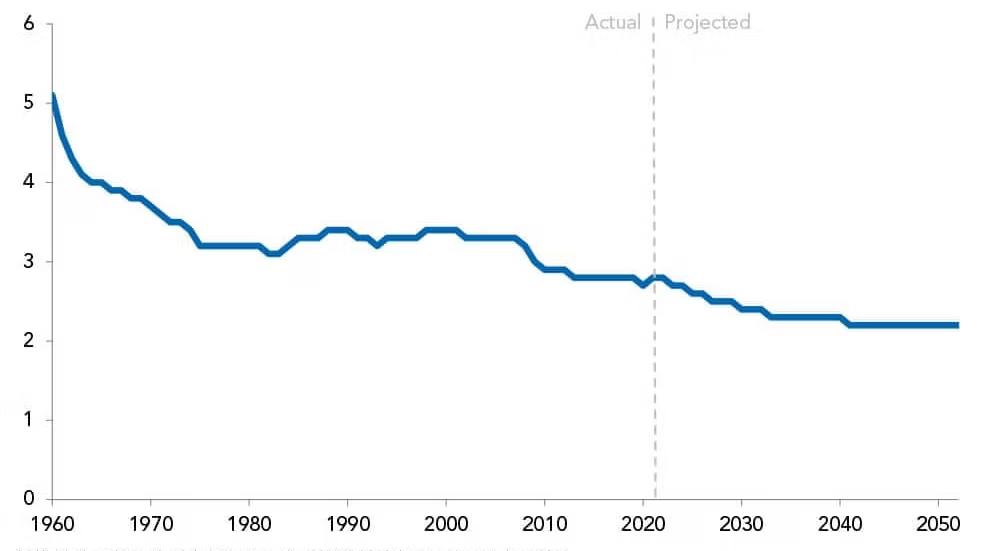

| Workers per Beneficiary (2025) | 2.7 workers supporting each retiree, down from 5.1 in 1960 |

| Official Website | Social Security Administration |

A System Under Strain

For decades, Social Security has been the backbone of American retirement security, providing income to more than 70 million retirees, disabled workers, and survivors. Yet the system was designed in the 1930s, when people lived shorter lives and the workforce was growing rapidly.

Today, the math has changed. Americans are living longer, fertility rates are lower, and the ratio of workers to retirees continues to shrink. That means fewer payroll contributions supporting a growing number of benefit payments.

According to the latest trustees’ projections, the combined Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) and Disability Insurance (DI) funds could be exhausted by 2034. After that, the incoming payroll taxes would still cover roughly 80 % of promised benefits—but not all.

“This is not a collapse,” said Dr. Elaine Morris, a senior economist at the Center for Retirement Research. “It’s an automatic adjustment built into the law, but it means retirees could face sudden cuts if Congress does nothing.”

The 2026 COLA: Relief Today, Reality Tomorrow

Starting in January 2026, recipients will receive a 2.8 percent increase in monthly payments. The average retired worker will see about $56 more per month, bringing the typical benefit close to $2,080.

However, many analysts say the adjustment is unlikely to keep up with inflation in essential goods—especially healthcare, rent, and food. Senior advocacy groups have described the raise as “helpful but insufficient.”

For retirees living primarily on Social Security, even small increases in living costs can erode purchasing power quickly.

“COLAs help, but they don’t solve the bigger issue,” said Nancy Klein, policy director at the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare. “The system itself needs modernization to reflect today’s economy and demographics.”

Why the Shortfall Exists

Several structural and demographic forces are converging to weaken the system’s finances:

- Aging Population: By 2030, all baby boomers will be at least 65 years old. Roughly 10,000 Americans reach retirement age every day.

- Longer Life Expectancy: The average American who reaches age 65 can expect to live another 19 to 20 years, up from about 13 years in 1940.

- Declining Birth Rate: Fewer workers are entering the labor force to replace retirees, reducing payroll tax revenue.

- Wage Inequality: A larger share of total income now goes to high earners, but earnings above the taxable cap (set to rise to $184,500 in 2026) are not taxed for Social Security.

- Policy Expansions: Recent legislative adjustments—such as eliminating offsets that limited certain public employees’ benefits—have expanded payouts without adding equivalent new revenue.

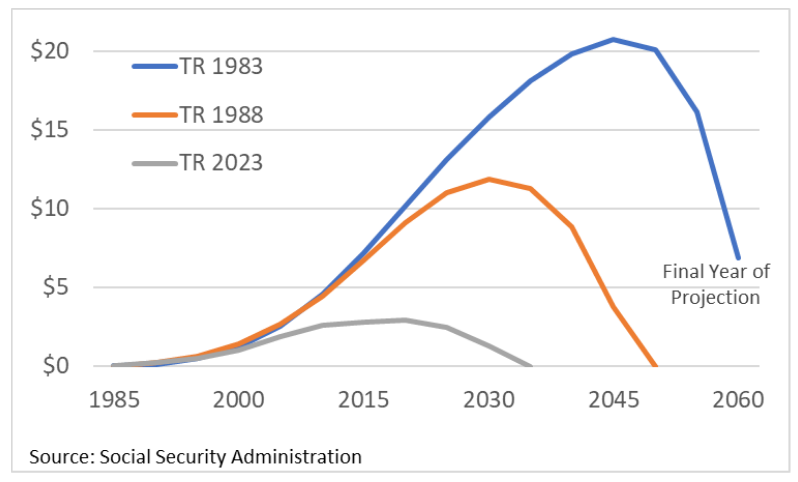

In short, the program now spends more each year than it collects. In 2025, Social Security paid out about $1.5 trillion in benefits while collecting around $1.4 trillion in revenue. The difference is covered by drawing down trust fund reserves, which currently hold about $2.5 trillion in Treasury securities.

Possible Fixes—and Their Trade-Offs

1. Raise Payroll Taxes

One of the simplest options is to raise the payroll tax rate, now 12.4% of wages (split evenly between employers and employees). Analysts estimate that raising it to about 16.2% would close the 75-year funding gap.

However, this approach is politically sensitive. Lawmakers are reluctant to raise taxes on workers, particularly lower-income earners already struggling with inflation.

2. Lift or Eliminate the Taxable Cap

Currently, only wages up to $184,500 are subject to Social Security taxes. Lifting this cap—or eliminating it for incomes above $400,000—would boost revenue without affecting middle-class workers.

Proposals in Congress have suggested a “donut hole” approach: taxing earnings up to the cap, exempting middle incomes, and reapplying the tax for very high earners.

3. Adjust Benefits Gradually

Policymakers could trim benefits for future retirees by indexing them to inflation rather than wage growth, which would slow benefit increases over time. Raising the full retirement age beyond 67 is another frequently discussed option.

Such changes would give younger workers time to adapt while sparing current retirees from abrupt reductions.

4. Diversify Funding Sources

Some economists advocate partially funding Social Security through general revenues or investment of trust funds in diversified assets rather than exclusively in U.S. Treasury bonds. Proponents argue that broader investment could yield higher returns; critics warn it would expose the program to market risk.

Political Stalemate in Washington

Both major parties acknowledge the looming problem but differ sharply on solutions.

- Democrats generally favor raising the payroll cap and preserving or expanding benefits, arguing that retirees should not bear the cost of demographic shifts.

- Republicans emphasize long-term spending control, preferring gradual benefit changes and potential private-savings incentives to reduce reliance on federal programs.

So far, there is no bipartisan consensus. Previous attempts—such as the 1983 Reagan-Tip O’Neill compromise that stabilized the system for four decades—remain a historical model for how cooperation could work again.

Without legislative action, automatic benefit reductions would take effect once reserves are depleted.

What It Means for Retirees

For the 51 million retired workers currently receiving benefits, the message is mixed. Payments are secure in the near term, but the long-range outlook suggests planning ahead.

If the trust fund runs dry, the average retiree could see a reduction of roughly $350 to $400 per month from current benefit levels. That would be a major blow, especially since nearly half of retired Americans rely on Social Security for at least half of their total income.

“For someone living on a fixed income, a 20 percent cut isn’t abstract—it’s rent, medicine, or groceries,” said Dr. Kenneth Li, professor of public policy at the University of Maryland.

Impact on Younger Generations

Younger workers face a more uncertain future. Millennials and Gen Z will likely pay more into the system while receiving proportionally less in return. Many financial planners now recommend that younger workers assume they’ll receive only about 75-80% of their projected benefits when planning for retirement.

At the same time, distrust in the program is growing. Surveys show that only about one-third of Americans under 40 believe Social Security will provide meaningful benefits by the time they retire. This perception could affect savings behavior and even political participation.

Economic and Social Consequences

A reduction in Social Security benefits could ripple far beyond retirees. Lower benefits would likely suppress consumer spending among older Americans, a demographic that accounts for nearly one-fifth of all U.S. consumption.

Additionally, delayed retirements could slow job openings for younger workers, tightening the labor market. States might also face higher demand for assistance programs such as Medicaid and Supplemental Security Income (SSI).

“Social Security isn’t just a retirement check,” said Maria Torres, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “It’s a stabilizer for the entire economy. When seniors spend less, local economies—from grocery stores to healthcare providers—feel it immediately.”

Practical Steps for Individuals

Financial planners and economists alike offer similar guidance:

- Review your Social Security statement each year for accuracy.

- Delay claiming benefits if possible—waiting until age 70 increases monthly payments by roughly 8 percent for each year beyond full retirement age.

- Build diversified savings through 401(k)s, IRAs, and investments to reduce dependence on public benefits.

- Plan for longevity, assuming you could live well into your 80s or 90s.

- Monitor policy changes in Washington and adjust your plans as new legislation evolves.

Historical Context

This is not the first time the program has faced a crisis. In the early 1980s, the trust fund was within months of depletion before lawmakers reached a last-minute bipartisan deal. That reform package gradually raised the retirement age, increased payroll taxes, and temporarily taxed some benefits.

The 1983 agreement restored solvency for roughly 50 years. Experts say a similar mix of modest adjustments today could stabilize the system for another half-century—if implemented soon.

Looking Ahead

Economists warn that delay carries real costs. Each year of inaction increases the eventual adjustments required. If reforms were enacted now, smaller tax increases or slower benefit changes could close the gap. Waiting until 2030 or later could force abrupt cuts.

“The math is simple,” said Dr. Morris. “Fixing Social Security now would be like adjusting the course of a ship early. Waiting until the iceberg is visible means the turn will be too sharp—and someone gets hurt.”

For most Americans, the harsh truth is that Social Security remains solid today but unsustainable tomorrow. The challenge is not whether the system survives—it will—but whether it continues to deliver on its promise of retirement security for all.