Starting January 2026, millions of Americans will receive a Social Security raise of approximately 2.8 per cent, but many beneficiaries may see little or no net increase after rising healthcare premiums and other deductions are applied. Experts say the deeper dynamics of inflation, mandatory costs and benefit formula limitations are the true story behind what appears to be a meaningful boost.

2.8% Social Security Raise

| Key Fact | Detail / Statistic |

|---|---|

| Projected COLA (Cost-of-Living Adjustment) for 2026 | ~2.8 % increase in benefits |

| Estimated average monthly increase | Roughly $56 per month for the average retired worker |

| Projected rise in Medicare Part B premium | Up about 11.6 % (roughly $21.50/month increase) |

| Real cost inflation in major retiree expenses | Healthcare and housing rising faster than 2.8 % |

| Official Website | Social Security Administration |

The Raise in Nominal Terms

The Social Security Administration has confirmed that benefits for retirement, disability and survivor beneficiaries will increase by 2.8 per cent beginning January 2026. This is derived from the annual cost-of-living adjustment (COLA), which is designed to help preserve purchasing power by tying benefit updates to inflation. The average boost translates to about $56 extra per month for a typical retired worker, given current benefit levels.

At first glance, a 2.8 per cent raise may seem modest but positive — especially relative to recent years of low inflation. But the critical question is: how much of that raise will actually reach beneficiaries’ bank accounts, and how far will it stretch against rising costs?

Why It Feels Smaller Than It Appears

Medicare Premiums and Mandatory Deductions

For many beneficiaries, much of the nominal raise will be consumed by higher mandatory costs — especially the premium for Medicare Part B, which is automatically deducted from Social Security checks for most enrollees. Analysts project the standard Part B premium to jump by about 11.6 per cent, representing roughly a $21.50 per month increase.

Since this deduction comes out of the Social Security benefit itself, the “take-home” gain may shrink substantially. For example, if the gross raise is $56 but the premium deduction increases by $21.50, the net gain would be around $34.50 per month — about 60 % of the headline raise.

Further, the effect is even larger for lower-income retirees whose total benefit is small: in some cases the deduction may consume all of the COLA, leaving zero net increase.

Inflation and Spending Patterns of Older Americans

The method used to calculate the COLA (based on the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers, or CPI-W) may not fully reflect the actual inflation faced by older Americans. According to researchers, older households typically spend more on healthcare, housing and prescription drugs — areas where inflation has been higher than the overall CPI-W.

Analysts estimate that using an alternative index — the Consumer Price Index for the Elderly (CPI-E) — would produce a higher COLA (on average about 0.2 percentage points more per year) because it assigns greater weight to senior-relevant expenses.

How the COLA Is Calculated — and Why It Matters

The Formula Behind the Raise

Under current law (see the Social Security Act of 1935, as amended), the COLA is based on the increase in the average CPI-W from the third quarter (July through September) of the prior year to the third quarter of the current year. The resulting percentage becomes the benefit increase for the next calendar year.

For example, if the average CPI-W for July-Sept 2024 is 308.7 and for July-Sept 2025 is 318.0, the percentage change (roughly 3.0 per cent) would determine the COLA for benefits payable starting January 2026.

Why Alternative Indexes Are Under Discussion

Advocates for using the CPI-E argue the current formula under-counts inflation faced by older adults. A Congressional Research Service (CRS) study found that the CPI-E would have raised the COLA by about 0.5 percentage points in recent years compared to the CPI-W.

However, shifting to a broader index could raise long-term costs for the system. Analysts at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College estimate that adopting CPI-E would increase the 75-year actuarial shortfall by roughly 12 per cent.

The Numbers: What It Means for Beneficiaries

Gross vs. Net Impact

Let’s walk through a hypothetical scenario for clarity:

- A retiree currently receives $2,000 per month.

- A 2.8 % raise would add $56, bringing the gross to $2,056.

- If the Medicare Part B premium grows by $21.50/month (automatically deducted), the check drops to roughly $2,034.50.

- That’s a net increase of about $34.50 — less than two-thirds of the headline raise.

The “Hold Harmless” Rule

There is a regulatory safeguard known as the hold harmless provision, which protects certain beneficiaries (primarily those aged 65+ and enrolled in Medicare) from having their net Social Security benefit reduced solely because of a higher Part B premium. Instead, their raise may be fully absorbed into the premium increase, but their check won’t go down.

This rule provides limited relief — it prevents a cut, but does not guarantee a real increase in purchasing power.

Impact Across Income Groups

Smaller benefit recipients and those with lower incomes are hit hardest in proportional terms. For someone receiving, say, $800 per month in Social Security, a $21.50 deduction could wipe out their entire gross raise (if the raise is ~$22 or so).

Conversely, higher-income retirees (who do not pay the standard premium deduction, or who have different cost structures) may fare better, though they still face inflation and healthcare cost risks.

Broader Policy and Fiscal Context

Solvency Pressures on Social Security

The Social Security program is facing long-term fiscal pressures. According to the Board of Trustees, the combined trust funds for old-age, survivors, and disability insurance are projected to be depleted by approximately 2035, after which incoming tax revenue would only cover about 77 per cent of scheduled benefits unless Congress acts.

In that context, even modest raises such as the 2.8 per cent are part of a delicate balancing act: providing cost-of‐living protection, while preserving reserve funds and not driving up deficits.

The Healthcare Cost Shift

Healthcare costs — including premiums, deductibles, and prescription drugs — are rising at a faster rate than general inflation. For example, the standard Part D deductible is expected to increase from $590 to $615 in 2026.

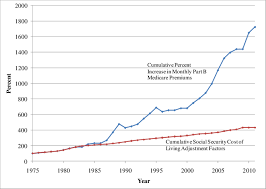

Because older Americans spend a larger share of their budget on healthcare, the mismatch between the COLA (based on broader inflation) and their actual cost growth is increasingly significant. Researchers attribute a growing erosion of “real benefit value” even when nominal benefits rise.

Legislative Proposals and Reform Ideas

Several proposals are under discussion in Congress, including:

- Switching the COLA index from CPI-W to CPI-E to better reflect older Americans’ inflation experience. Proponents say this would raise benefits modestly over time.

- Reforming Medicare premium rules and deduction structures to reduce the immediate offset of the COLA by mandatory costs.

- Adjusting eligibility, tax bases, or benefit formulas to preserve program solvency while maintaining benefit adequacy.

Opponents of switching to CPI-E caution that without offsetting funding measures, higher benefits would accelerate the depletion of the trust fund.

Practical Take-Aways for Beneficiaries

- Review your estimated 2026 check when the SSA statement arrives (typically December) and compare your gross benefit increase to net amount after expected deduction changes.

- Prepare for higher healthcare costs: aside from premiums, out-of-pocket expenses, deductibles and drug costs may rise. Budget accordingly.

- Adjust spending plans: Even a net monthly increase of $30-$40 may not cover inflation in housing, utilities, food or medical care — larger cost risks remain.

- Monitor policy changes: Keep an eye on legislative developments in COLA indexing or Medicare premium reforms, which could affect future years.

- Explore supplemental income or savings strategies: If Social Security is a substantial part of your income portfolio, building alternatives or buffer funds may help mitigate cost pressures.

A Deeper Historical View

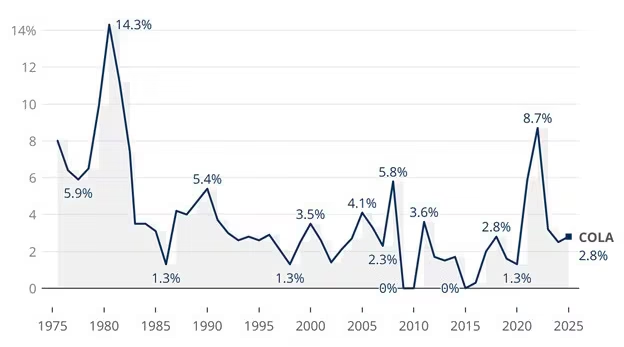

Since the introduction of automatic COLAs in the early 1970s, the annual benefit increases have varied widely. For example:

- 2023 saw a historic 8.7 per cent COLA amid post-pandemic inflation.

- 2024’s increase dropped to 3.2 per cent.

- 2025’s increase was 2.5 per cent.

The 2026 projected figure of 2.8 per cent fits the trend of lower inflation and correspondingly lower benefit increases.

Over the long term, the average COLA since 2010 has been about 2.3 per cent annually.

During periods of high inflation, retirees have benefited more significantly — but even then, the rise in healthcare or housing often kept pace or exceeded those increases.

Why Understanding This Matters

For millions of Americans, the annual Social Security raise is a key component of retirement income planning. While a 2.8 per cent raise may look like positive news, the broader context reveals that the real value of that raise may be limited once mandatory cost increases are factored in.

$1000 Hits Alaska Bank Accounts November 20—But Only If You Meet These Hidden Requirements

By understanding how the raise is calculated, what deductions or offsets apply, and where cost pressures are most acute, beneficiaries can better prepare, adjust expectations and plan accordingly.